Another Paper. I feel lazy.

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is unique in literature as a book whose true villain is a theory in the mind of its protagonist. This theory of the ubermensch, or superman, is originated by the main character, Raskolnikov, who essentially claims that any breach of the moral law is permitted to those few “extraordinary men” who are destined to bring an increase of the overall justice of the world. Obsessed with this theory, Raskolnikov’s mind becomes dramatically conflicted, his good inclinations at variance with his desire to prove himself one of these ubermensch. Despite this obsession, the ramifications of his idea remain unclear to Raskolnikov until he meets the man, Svidrigailov.

Svidrigailov is a figure whose presence throws Raskolnikov’s mental split into sharp relief by his own unwavering singleness of purpose. This man, in fact, epitomizes the theory that creates Raskolnikov’s mental turmoil in the first place. He lives for a single purpose – himself – and seems immune to moral responsibility. He is superficially suave and polite. As Raskolnikov tells him, I fancy indeed that you are a man of very good breeding, or at least know on occasion how to behave like one.” (Part 4, Chapter 1 -p.256) However, this “good breeding” is a rather thin disguise for a character so absorbed with his own comfort and pleasure that he has become utterly depraved. He is calm and rarely loses his temper, but his composure often hides plotting and conniving. He has committed several murders over the space of many years. But in accordance with the idea that the extraordinary man would merit no temporal or mental punishment, he is completely remorseless. Moreover, he is above human law, because the nature of his crimes is such that they can never be proven.

Raskolnikov’s character is an interesting mix of good and bad traits; his generosity, compassion, and love for justice contrast sharply with his sullenness, morose attitude, and pride. His close friend Razumihin describes him as “morose, gloomy, proud and haughty…He has a noble nature and a kind heart… it’s as though he were alternating between two characters.” (Part 3, Chapter 2 – p.194) Up to the point of the meeting with Svidrigailov, Raskolnikov is plagued with guilt for the murder of an old pawnbroker whose dishonesty, he had decided, had “deserved” death. The better side of his character makes it impossible for him to escape this guilt; however, the only conclusion he will admit is that he is not an extraordinary man. The idea that his theory may be wrong is intolerable to his pride – even if he is one of the “worms” of the world, bound by moral laws and human regulations, his idea at least must be right.

But then Svidrigailov introduces himself to Raskolnikov, insisting from the opening moments of their conversation that he and the younger man are unnervingly alike, despite the fact that Raskolnikov is as outwardly brash, rude, and quick tempered as Svidrigailov is cool, polite, and calm. “Didn’t I say there was something in common between us? ...... Wasn’t I right in saying that we were birds of a feather?” (Part 4, Chapter 1) Raskolnikov reacts indignantly to the idea. Svidrigailov has crimes in his past as well, but his crimes were far from Raskolnikov’s “just murders” – this man had caused the suicide of a deaf girl of fifteen, he had caused the death of one of his servants, and he had most likely poisoned his own wife. Each of Svidrigailov’s actions is calculated for no purpose beyond his own pleasure - his existence is purely selfish. Raskolnikov at least has a noble purpose at heart; or so he protests at first. However, the idea that he, Raskolnikov, is somehow more just than this other murderer disappears quickly when Rodion realizes the truth which the reader has perhaps seen all along. Svidrigailov is simply the extreme of the “extraordinary man” Raskolnikov has been turning himself into over the course of several horrible months. Despite the differences in outward personality, Raskolnikov is indeed becoming similar to Svidrigailov, the extraordinary man.

True, Svidrigailov’s aims and motives are ostensibly quite different from the protagonist’s. They seem worse perhaps, because they seem more selfish. But is that appearance true? Raskolnikov kills the old woman with the sanction of his concept of justice, but why else does he kill in the first place except to prove his status as one of the ubermensch? It is hardly less selfish to commit a crime in order to satisfy one’s pride than it is to do the same in pursuit of physical pleasure. And how even can Raskolnikov’s initial perception of his crimes being superior in the realm of justice be given exceptional credence? Svidrigailov may cause deaths that seem totally unjust from the standpoint of human morality, but the first premise of the ubermensch theory is that extraordinary men are not bound by these standards. Such men “have the right” to interpret aims and means of achieving the greater good. Svidrigailov is undeniably a superman by Raskolnikov’s definition, and he thinks that he himself is the greater good, making his “selfish” actions perfectly justifiable by the theory’s standards.

There are, Raskolnikov comes to realize, two possible solutions to the questions raised by this perfect ubermensch. Svidrigailov might be a good man, in accordance with the theory. The idea is abhorrent to any honest person. Even Svidrigailov, in fact, recognizes that he is not a good man – he admits his depravity easily, although he feels no remorse for it. He recognizes even, that he is not a healthy man. He has seen ghosts, he says, and ghosts “are unable to appear except to the sick” (Part 4, Chapter 1 – p.260), the healthy are too much a part of reality to be bothered by such supernatural beings. Svidrigailov goes on to muse that once he really leaves this world, he can expect nothing better than “one little room, like a bathhouse in the country, black and grimy and spiders in every corner.” (Part 4, Chapter 1 – p.261) Raskolnikov responds with as much horror as he did to the idea of his similarity to Svidrigalov. “Can it be you can imagine nothing juster and more comforting than that?” (ibid.) Svidrigailov’s response reveals not only his own self-condemnation, but also the emptiness of promise and hope in ubermensch morality. “Juster? And how can we tell, perhaps that is just, and do you know, it’s certainly what I would have made [eternity].” (ibid.)

If the possibility of Svidrigailov’s “goodness” (and thus the possibility of the goodness of any such superman) is so roundly contradicted, there is only one other possibility. That is, the ubermensch theory must be wrong. As Raskolnikov thinks things over, wrestling with his pride, he begins to come to this conclusion. It eventually becomes apparent to him that the second really is the only sensible possibility, the only possibility which fits in with human nature, and the only possibility that promises something more just than a petty eternity filled with spiders. With this admission, he finally begins to renounce his pride and self-righteousness.

Indeed, the encounter with Svidrigailov, the epitome of Raskolnikov’s negative qualities, instigates the protagonist’s first real swing towards repentance. By being faced with the true face of his theory he is compelled to admit its repulsiveness. In the process, he is obliged to open the door to his own redemption by admitting that he is a criminal, that he must submit to the human justice he disdained for so long, and that he must find peace in the hope of God’s mercy.

25 June, 2007

21 June, 2007

Good Poetry

I'm still reading through T.S. Eliot's anthology of poetry, despite the fact that I've already graduated and am finished with the readings I was assigned in that book. It's the sort of poetry that catches hold of you and won't let you ignore it for some time. I leave the book each time with a profound respect for Eliot's poetic mastery, then come back and realize how meanly I've shortchanged his accomplishments.

One thing that strikes me each time I read one of his poems is the incredible economy of language. He never puts in a word that adds nothing to the meaning. Rather, the poems consist of the meaning itself, pared down to the most essential language. All really good poetry that I've read seems to be like this, actually. I don't pretend to be at all knowledgeable on the subject - I neglected poetry (except for that of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear) dreadfully until I read the "Raven" two years ago. But it seems to me that this brevity packed with meaning is the essence of good poetry. The varying structures, clever or original use of language, etc, are all only useful when they add something to the meaning of the poem. They're simply tools for the poet to use in order to pare all superfluity out of his ideas.

It is funny that the most common depiction of a poet I've ever found in movies and books (a prose writer must be much different from a poet, I think) is of a rather muddle-headed, overly sentimental person, whose head is floating randomly through the clouds. But if you think about it, a really good poet must be more clear headed and practical than all the rest of us. He or she should be able to see through common phrases and ways of thinking to get at the very root of things, and to express them without writing a thousand-page philosophical tome.

The only really frivolous type of poetry is bad poetry. Bad poetry is poetry in which the poet is laconic because that happens to be the fashion, or flowery because he or she is really more of a lover of language than a poet, per se. It also has something to do with the poet's ability to express himself accurately, of course. The first problem I mentioned in this paragraph has to do with lack of a poet's mind. This one has to do with lack of a poet's craft. If you have brilliant insights into the human condition, but can't use language well enough to express meaning with really poetic brevity and facility, you may have the mind of a poet, but you'll have to settle for being a philosopher.

One thing that strikes me each time I read one of his poems is the incredible economy of language. He never puts in a word that adds nothing to the meaning. Rather, the poems consist of the meaning itself, pared down to the most essential language. All really good poetry that I've read seems to be like this, actually. I don't pretend to be at all knowledgeable on the subject - I neglected poetry (except for that of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear) dreadfully until I read the "Raven" two years ago. But it seems to me that this brevity packed with meaning is the essence of good poetry. The varying structures, clever or original use of language, etc, are all only useful when they add something to the meaning of the poem. They're simply tools for the poet to use in order to pare all superfluity out of his ideas.

It is funny that the most common depiction of a poet I've ever found in movies and books (a prose writer must be much different from a poet, I think) is of a rather muddle-headed, overly sentimental person, whose head is floating randomly through the clouds. But if you think about it, a really good poet must be more clear headed and practical than all the rest of us. He or she should be able to see through common phrases and ways of thinking to get at the very root of things, and to express them without writing a thousand-page philosophical tome.

The only really frivolous type of poetry is bad poetry. Bad poetry is poetry in which the poet is laconic because that happens to be the fashion, or flowery because he or she is really more of a lover of language than a poet, per se. It also has something to do with the poet's ability to express himself accurately, of course. The first problem I mentioned in this paragraph has to do with lack of a poet's mind. This one has to do with lack of a poet's craft. If you have brilliant insights into the human condition, but can't use language well enough to express meaning with really poetic brevity and facility, you may have the mind of a poet, but you'll have to settle for being a philosopher.

17 June, 2007

Graduation

So, I semi-officially graduated today, I suppose. We had a joint graduation celebration with some of our friends down in Portland today. I say semi-officially only because my schoolwork has not yet been sent to California for Kolbe Academy to okay, and because of that, I haven't received my official diploma.

As it was, the official party for the semi-official graduation was heaps of fun, involving lots of good food and contra dancing.

My family was largely in charge of the food. Mama and Mary made five enormous lasagnas, plus a titanic bowl of salad. If I'm not mistaken, the house still smells distinctly of the former. (It's very possible with my allergies that I am mistaken, and it's all in my head.) I actually still haven't tasted the lasagna, since my lunch for some reason ended up consisting of Greek olives and carrots. But I don't think I'll be able to escape doing so eventually (the lasagna is tasty, don't get me wrong; the narrator simply isn't a huge fan of tomato sauce): even though we practically threw the stuff at people as they were leaving, we still have tons leftover (we'd made enough for over a hundred people, just to be safe, and not that many came).

Contra dancing is fun. Very fun. It rather reminds me of the Jane Austen era dances, with a few differences.

1. The music can be similar in style, but is definitely livelier. It's usually Irish or French Canadian fiddle music, so some of the roots are similar, but other than that, the main resemblence is in their mutual dissimilarity to current popular dance music.

2. It's much less organized. In Jane Austen's times, people knew the dances, for the most part. Now they don't.

3. It's very informal: people don't care if you dance with your 4-year-old brother; just having fun is what matters. (With some restrictions, of course.......... You don't want to appear a complete idiot.)

As it was, the official party for the semi-official graduation was heaps of fun, involving lots of good food and contra dancing.

My family was largely in charge of the food. Mama and Mary made five enormous lasagnas, plus a titanic bowl of salad. If I'm not mistaken, the house still smells distinctly of the former. (It's very possible with my allergies that I am mistaken, and it's all in my head.) I actually still haven't tasted the lasagna, since my lunch for some reason ended up consisting of Greek olives and carrots. But I don't think I'll be able to escape doing so eventually (the lasagna is tasty, don't get me wrong; the narrator simply isn't a huge fan of tomato sauce): even though we practically threw the stuff at people as they were leaving, we still have tons leftover (we'd made enough for over a hundred people, just to be safe, and not that many came).

Contra dancing is fun. Very fun. It rather reminds me of the Jane Austen era dances, with a few differences.

1. The music can be similar in style, but is definitely livelier. It's usually Irish or French Canadian fiddle music, so some of the roots are similar, but other than that, the main resemblence is in their mutual dissimilarity to current popular dance music.

2. It's much less organized. In Jane Austen's times, people knew the dances, for the most part. Now they don't.

3. It's very informal: people don't care if you dance with your 4-year-old brother; just having fun is what matters. (With some restrictions, of course.......... You don't want to appear a complete idiot.)

14 June, 2007

Narn I Chin Hurin - The Story

To get back to the Children of Hurin...

The story is dark, make no mistake about that. And if you thought the Lord of the Rings, with its Orcs and Ringwraiths and deaths of major characters and nearly-failed quests was dark, I don't know what you'd call this. "The negation of light"? "If you could get below absolute zero on the Kelvin scale, this is what it might be like"? ---- No, not quite as dark as that last one.

It's not depressing, oddly enough. A rather clean darkness, this seems to be, not without hope even at the worst moments. I might say that it's tinged, just in tone, with the Catholic idea that everything is able to be saved. I don't want to give the idea that it's religious at all. The background and plot of the story, and even to a large degree the morality of the heros, is much closer to that of the North European pre-Christian epics. Often the tone recalls the Finnish Kalevala or the Volsunga Saga or just general Norse mythology. A few parts even reminded me irresistably of Beowulf (yes, that was by a Christian author, but one like Tolkien in more ways than one).

The biggest difference from the Norse myths or the pagan epics lies in something which at first they appear to share in common: the driving force of a curse (or fate) and its effects on the heroes.

I hope it won't ruin the story for anyone if I mention that the Hurin of the title starts off the story by gaining the particular emnity of Morgoth. (For those who aren't familiar with the Silmarillion: if you want an idea how bad Morgoth was, you should know that Sauron - the grand bad guy of the Lord of the Rings - was at this time only Morgoth's lieutenant.) To get back at Hurin, Morgoth curses the poor guy's family.

The entire tale is simply the story of how this curse works out; of how Morgoth's object is achieved. And it is in this that the story is rooted in a more Catholic view of life. Because unlike pagan mythology, the curse here never directly controls the fate of either of Hurin's children. Rather, Morgoth has to work actively to bring about its effects.

He does this by playing on Hurin's son, Turin's, weaknesses - weaknesses such as pride and impulsiveness - till these become the prominent features of Turin's character. Eventually, Turin (and to a lesser degree, the more minor character of his sister, Nienor) becomes the primary agent of his own family's destruction.

The difference I keep talking about lies in the fact that never does this destruction become inevitable. Turin continually brings it on through his own choices. Although Morgoth brings about many of the book's critical situations, Turin (or Nienor, or Morwen, their mother) make the choices which cause the real tragedy and the darkness of the book. And this tragedy is simply the fact that the characters play into Morgoths hands, giving him the advantage of a moral as well as physical victory over the children of Hurin.

13 June, 2007

"Internet breathes life into dying languages"

Papa sent me this article, knowing that I have a large interest in endangered languages. If you think, as I do, that language is a crucial part of culture, you can understand the interest, probably. For instance, who'd really want the Irish culture watered-down with a heavy Anglo-Saxon influence when you could keep the language and keep the Celtic roots of the culture?

By Amie Ferris-Rotman

HOLYHEAD, Wales, June 12 (Reuters Life!) - Endangered languages like Welsh, Navajo and Breton have regained speakers and popularity in their communities and are now even "cool" for kids -- thanks to the Internet.

Welsh language expert David Crystal said the Internet could forestall the dismal fate of about half of the world's 6,500 languages, which are doomed to extinction by the end of the 21st century at a rate of about two language deaths a month.

"The Internet offers endangered languages a chance to have a public voice in a way that would not have been possible before," said Crystal, who has written over 50 books on language including "The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language".

Languages at risk of extinction are appearing on blogs, instant messaging, chat rooms, video site www.youtube.com and social networking site www.myspace.com, and their presence in the virtual world curries favor with youngsters who speak them.

"It doesn't matter how much activism you engage in on behalf of a language if you don't attract the teenagers, the parents of the next generation of children," Crystal, who was raised speaking English and Welsh, told Reuters.

"And what turns teenagers on more than the Internet these days? If you can get a language out there, the youngsters are much more likely to think it's cool."

Online free Encyclopedia www.wikipedia.org, written and built by volunteers, has entries in dozens of endangered languages, from native American Cherokee to the Austronesian language Tetum, spoken by less than a million people in East Timor, to the Maori language of New Zealand.

Tens of Welsh chat rooms exist for its 600,000 speakers -- just over 20 percent of Wales -- where young people look for the best pubs in town, or hunt for potential dates.

Crystal said there are 50-60 languages in the world which have one last speaker, and around 2,000 have never been written.

"If these languages die, they are gone forever. This is a huge intellectual loss to humanity. The Internet is very important in this respect," he said.

Money is usually required to go virtual however, and this is problematic for African and indigenous South American languages, where resources are low and governments favor dominant languages Spanish, French and English.

Native American languages, especially Navajo, are fortunate to have many virtual communities on the Internet as most are funded by the lucrative casinos the Navajos run, Crystal said.

"To put it into perspective only two to four percent of the world's botanical and zoological species are in serious danger, whereas it's 50 percent of languages. The language crisis hasn't attracted the same degree of public awareness".

Narn I Chin Hurin - Improved Edition

I'm a huge Tolkien fan, as anyone acute enough to notice the title of this blog has probably guessed. So for me, one of this year's most highly anticipated events has been the release in book form of Tolkien's long partially-published Narn I Chin Hurin, or "The Tale of the Children of Hurin."

The tale is one of the three major myths (beyond the Lord of the Rings) that Tolkien wrote, the other two being The Tale of Beren and Luthien and The Fall of Gondolin. All three can be found in basic form in the Silmarillion, Tolkien's immense master-mythology of Middle Earth. A more extended version of each is also found in The Book of Lost Tales, and from what I understand, in The History of Middle Earth as well. (I haven't read this last one.) So when I heard (back in October) that this book would be published this April, I promptly rushed to our bookshelves and re-read the tale in both the Lost Tales and in the Silmarillion.

The content of the published tale was not surprising, then, for me. I was, however delighted to find several chapters with parts of the story I had not encountered in either version. I'm not sure if these came from Tolkien's unpublished notes, but that's what I assumed at the time. The best part of re-reading it in a form edited together into one storyline was the improved continuity of the story. The version in the Book of Lost Tales was unfinished; the version in the Silmarillion was too brief in areas to make a good stand-alone story. This was much easier to read, since there was no need to skip from book to book, piecing the story together on my own.

It was well worth the re-reading just for these reasons. I'll write about the story itself next, hopefully soon.

08 June, 2007

Museum of Fine Arts

Conclusions from yesterday: 1. Boston is way bigger than I had realized. 2. The sheer volume of people in really big cities is astonishing. 3. Greek food is incredibly tasty. 4. The Museum of Fine Arts is a mind-bogglingly beautiful place.

So, Papa took me, Mary, and five friends down to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston yesterday. We spent the day walking - around the museum, around Boston sidewalks, through the Prudential Building, back and forth to various chapels, etc. All very fun. But I won't describe anything but the museum in further detail here, because this is supposed to be a blog with a theme, rather than a travelogue.

My favorite paintings were by far the Impressionist ones, although I only got a very brief look at most of those. We rushed through that exhibit on our way to lunch, intending to return later. What we didn't know was that certain exhibits occasionally close early, and that this was one of them on that day. A small disappointment. But I did get a chance to see a few real Monets. Monet is my most favorite artist, and some of his paintings were in other rooms. I also managed to glimpse one of my favorites of his work: one of the Cathedral paintings. (This was part of a series of paintings he made of the same building, from the same perspective, with variations only in lighting. A really magnificent set, I think.)

I'm too lazy to write any deep thoughts on the nature of art right now, so I'll just post some of my favorite pictures and let them speak for themslves.

Monet, La Japonaise

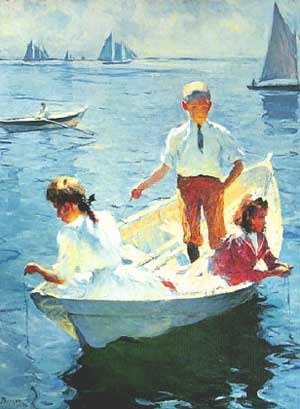

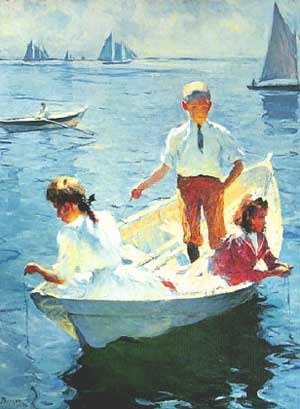

Frank Benson, Calm Morning

Thomas Sully, The Torn Hat

Oh, and I have to mention the book shop we stopped by. I think it was the oldest used book store in Boston... or at least it had some distinction of that sort. Anyway, a small outdoor sale was going on outside the shop, and I came across a set of 6 hardcover books by Dickens - his less well known works, like Martin Chuzzlewit, and The Old Curiosity Shop, and the Pickwick Papers - as well as a biography of St. Joan of Arc: all in very good condition and in the $1-a-piece section. Papa was then kind enough to lug the bag containing all seven around Boston for the next few miles. I didn't think of the carrying part when I bought them, I admit....

So, Papa took me, Mary, and five friends down to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston yesterday. We spent the day walking - around the museum, around Boston sidewalks, through the Prudential Building, back and forth to various chapels, etc. All very fun. But I won't describe anything but the museum in further detail here, because this is supposed to be a blog with a theme, rather than a travelogue.

My favorite paintings were by far the Impressionist ones, although I only got a very brief look at most of those. We rushed through that exhibit on our way to lunch, intending to return later. What we didn't know was that certain exhibits occasionally close early, and that this was one of them on that day. A small disappointment. But I did get a chance to see a few real Monets. Monet is my most favorite artist, and some of his paintings were in other rooms. I also managed to glimpse one of my favorites of his work: one of the Cathedral paintings. (This was part of a series of paintings he made of the same building, from the same perspective, with variations only in lighting. A really magnificent set, I think.)

I'm too lazy to write any deep thoughts on the nature of art right now, so I'll just post some of my favorite pictures and let them speak for themslves.

Monet, La Japonaise

Frank Benson, Calm Morning

Thomas Sully, The Torn Hat

Oh, and I have to mention the book shop we stopped by. I think it was the oldest used book store in Boston... or at least it had some distinction of that sort. Anyway, a small outdoor sale was going on outside the shop, and I came across a set of 6 hardcover books by Dickens - his less well known works, like Martin Chuzzlewit, and The Old Curiosity Shop, and the Pickwick Papers - as well as a biography of St. Joan of Arc: all in very good condition and in the $1-a-piece section. Papa was then kind enough to lug the bag containing all seven around Boston for the next few miles. I didn't think of the carrying part when I bought them, I admit....

06 June, 2007

Are Mythical Creatures Pagan?

Jolly, jolly ho! This is Goldbug. Therese was bugging me to post something, so here it is. I wimped out and decided not to write anything, so instead, I shall post a jolly good article on Mythology. I personally like Mythology, though these fools whom the article discusses don’t. I think that every person who doesn’t like Mythology should be beaten senseless by every able- bodied person in this blog. I wish I took Tae Kwon Do.

There. I just made myself out to be a very pugnacious person. Really though, on the serious side, I am an avid reader of Tolkien, Lewis, and L’Engle, and I agree with the following article, that many fantasy stories can “point readers toward goodness-and God.” Read on.

There. I just made myself out to be a very pugnacious person. Really though, on the serious side, I am an avid reader of Tolkien, Lewis, and L’Engle, and I agree with the following article, that many fantasy stories can “point readers toward goodness-and God.” Read on.

THE UNICORN HUNTERS

By SANDRA MIESEL

By SANDRA MIESEL“They’re drawing a bead on unicorns and the imagination. Shots come from many directions, and some of the nastiest originate at the fringes of Fundamentalism.

Author and Editor Jane Yolen, addressing the Society of Children’s Book Writers, deplored a rising tide of attacks on fantasy fiction. She observed that alarmists such as the widely-published Texe Marrs “insist that much of children’s literature–especially fantasy –is designed to encourage devil worship.”

Books, films, cartoon characters, games, and toys are denounced almost at random: Walt Disney fairy stories, the Smurfs, the Muppets, Dark Crystal (absurdly identified as a filmed version of The Lord of the Rings), the Care Bears, She-Ra and He-Man, the Star Wars trilogy, Rainbo Brite, The Secret Garden by Frances Hogsdon Burnett, Bunnicula by Deborah and James Howe, and works by C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Madeleine L’Engle, Zilpha Keatley Snyder, Bruce Coville, and works by Jane Yolen herself.

Leading the charge are Texe Marrs’s Dark Secrets of the New Age, Mystery Mark of the New Age, and Ravaged by the New Age–plus Berit Kjos’s Your Child and the New Age and Joanna Michaelson’s Like Lambs to the Slaughter.

The critics are armed with malevolent misinformation. For instance, in Ravaged by the New Age Texe Marrs excoriates the children’s cartoon show My Little Pony because it depicts unicorns, “a potent symbol of the third eye and the Antichrist, the little horn. Also note the double zigzag (’SS’) near the pony’s tail. This represent the seig rune, the pagan symbol of Satan.” (The word is spelled Sieg and means in German “victory,” and sometimes a zigzag is just that: a wavy line.)

This attitude turns up in books which don’t directly touch on fantasy literature. Even Catholics suffer from it. The prologue to Randy England’s The Unicorn in the Sanctuary “proves” the unicorn evil by mere assertion: “This mythical animal has often been associated in literature with both Christ (wrongly) and with Lucifer. It is not the cute and gentle creature popularly portrayed . . . but a symbol of tearing and trampling, breaking and crushing.”

Wrongly associated with Christ? By whom? England doesn’t say. Although a ghastly demon unicorn cribbed from Henry Fuseli’s masterpiece “The Nightmare” appears on his cover, unicorns aren’t mentioned in the body of England’s text. Their image is exploited as an attention-grabber for a thinly-researched book decrying New Age infiltration of the Catholic Church.

Although the unicorn is the favorite quarry, any mythical creature is fair game. Marrs fulminates against L’Engle’s critically and commercially successful fantasies because their covers depict a Pegasus-unicorn (A Swiftly Tilting Planet), a rainbow and a centaur (A Wrinkle in Time), and what he describes as a bird-man covered with eyes (A Wind at the Door). In the last case Marrs seems curiously unacquainted with cherubim, Ezekiel’s fourth living creature, or the traditional symbol for John the Evangelist. The texts of L’Engle’s books go unexamined, yet she’s attainted with guilt by association for having worked at the avant garde Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City.

Do these darts strike home? The public library of Fort Wayne, Indiana is reported to have issued a cautionary statement about L’Engle. Christian Book Distributors, a mail-order firm serving Evangelicals, finds its customers will buy other books by L’Engle, a devout Episcopalian, but not her fantasies. A few of its customers have questioned C. S. Lewis’s orthodoxy, presumably on the basis of attacks like Marrs’s.

These zealous anti-New Age critics argue that all pre-Christian and non-Christian symbols represent demonic evil and must be purged ruthlessly from Christian consciousness. It’s no accident that Michaelson scrupulously calls Easter “Resurrection Sunday.” (”Easter” has its etymological roots in the name of a pagan spring festival.)

This is emphatically not the traditional Catholic position. From the beginning, the Church has borrowed or “baptized” alien imagery for its own use. Hostility toward the fantastic bespeaks wider disagreement with basic Catholic attitudes toward works of culture.

A case in point: The much-maligned unicorn, which came to Western attention around 400 B.C. as a curiosity among Indian fauna, turns up in the Septuagint, the Vulgate, the King James, and the Douay translations of Scripture in contexts that connote glory, majesty, power, strength, and untamed freedom.

By A.D. 200, Tertullian called the unicorn a symbol of Christ. Ambrose, Jerome, and Basil agreed. The late-antiquity bestiary known as Physiologus popularized an elaborate allegory in which a unicorn tamed by a maiden stood for the Incarnation. This became the basic–and universal–medieval notion of the unicorn, justifying its appearance in every form of religious art.

The unicorn also acquired positive secular meanings, including chaste love and faithful marriage. (It plays this role in Petrarch’s Triumph of Chastity.) It was a heraldic motif, appearing on the national arms and coins of Scotland. The royal throne of Denmark was made of “unicorn horns” (actually narwhal tusks). The same material was used for ceremonial cups because the unicorn’s horn was believed to neutralize poison.

In more recent centuries alchemists made the unicorn represent “spirit.” It’s hard to see why this minority opinion renders the unicorn evil. If it does, why don’t the critics denounce the stag and the lion, which stand for “soul” and “body” in the same occult system?

As for other fabulous beings, Jerome’s Life of St. Paul the First Hermit includes a friendly centaur and a God-fearing satyr. Dante’s Divine Comedy shows a griffin drawing the triumphant chariot of the Church. The monster-slaying Bellerophon mounted on Pegasus was an early Christian symbol of Christ’s victory over Satan.

Dragons adore the Christ Child in a fourteenth-century French treatise, The Life of Our Blessed Savior Jesus Christ. The infant Jesus blesses them for honoring the divine command “Praise the Lord from the Earth ye dragons” (Ps. 148:7). Mermaids, giants, sphinxes, chimeras, and other fabulous creatures from pagan myth and folklore have decorated churches and other vehicles of religious art.

And let’s not forget the four creatures which traditionally have represented the four Evangelists: a winged man (Matthew), a lion (Mark), an ox (Luke), and an eagle (John).

If the unicorn hunters know any of this, they aren’t saying. Not only are they ignorant of such artistic basics, but they’re deficient in understanding how symbols mean. They assume each sign has a simple and unchangeable meaning which carries power in and of itself.

Some symbols are purely arbitrary: In a computer program such as the one used to compose this magazine, a dollar sign can indicate where a footnote is to appear. Other symbols have a more direct connection with the meanings they evoke: Water suggests cleansing, refreshment, fertility. Symbols are culturally conditioned and change with time. A swastika didn’t mean the same thing to an Aztec or an ancient Celt as it did to a Nazi–or as it does today to a Buddhist.

Since they wear such blinkers, it’s no wonder vigilantes attack fantasy haphazardly. Books by Marrs, Michaelson, and others make no effort to survey a representative sample of children’s literature, past or present. If books featuring magic and mysticism are always and everywhere evil, how can we permit children to touch stories by that atheistic, anti-Catholic Freemason and Nobel laureate Rudyard Kip-ling? Kim, Puck of Pook’s Hill, and Rewards and Fairies are stuffed with Eastern thought and paganism. And how about medieval romances, popular ballads, fairy tales, The Arabian Nights? Should impressionable high schoolers be exposed to Chaucer, Macbeth, or The Faerie Queen?

The ambivalence is evident in Berit Kjos. He’s willing to admit a nostalgia for traditional fairy tales, yet he condemns The Secret Garden for calling the protagonist’s cure “magic.” His seeing a dark design in Bunnicula, a comedy about a bunny which “vampirizes” vegetables, shows that Kjos’s capacity to interpret literature is not the only thing that is defective–so is his sense of humor.

Marrs’s paranoid, but profitable, jumble of misinformation deserves no serious attention. (He’s an ex-Air Force officer who’s built a prominent career as an evangelist trumpeting the bizarre allegation that all New Agers are part of a conscious, Satan-directed conspiracy bent on exterminating every Christian on Earth by the year 2004.)

Poor scholarship also undercuts the credibility of England (who relies heavily on the writings of the virulently anti-Catholic and sensationalism-rich Dave Hunt) and Michaelson’s complaints about New Age infiltration in schools and churches. Michaelson doesn’t cite Marrs yet copies his choice of targets, arguments, references, and even mistakes (for instance, calling the Egyptian sun-god Ra a goddess).

Her complaint about unicorns coyly alludes to “decidedly impure and unvirginal activities,” misrepresenting data from her source, Man, Myth and Magic, a popular but scarcely authoritative encyclopedia of the occult. Without justification or explanation, she prefers obscure uses of the unicorn and other symbols to their popular, public ones.

The unicorn hunters like to argue through inference and association, as when Michaelson speculates about the deep Hermetic learning of “kidvid” script writers or claims that the “shockingly violent and occultic role-playing game” Dungeons and Dragons is supposedly “based on Tolkien’s famous ‘Ring Trilogy,’ and has adopted a similar theme and feel.”

Michaelson apparently uses either the closest book or the one that gives the slant she wants. It’s difficult to image what possessed her to follow Marrs and base her treatment of Mesopotamian religion on Alexander Hislop’s anti-Catholic diatribe The Two Babylons or the Papal Worship (1853) or its recent rehash, Ralph Woodrow’s Babylon Mystery Religion (1966).

Hislop maintains that ancient Babylonian religion revolved around the worship of Nimrod and Semiramis and is perpetuated in Catholicism. Woodrow adds inane discussions of Mithraism.

In their relentless pursuit of the unicorn, the critics tend to take definitions or information from New Age sources at face value. They cite the New Age best-seller The Way of the Shaman by Michael Harner, but not the standard academic survey, Shamanism by Mircea Eliade. Or they quote The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets without correcting for its radical feminist agenda. They seem to be unacquainted with basic handbooks of myth and folklore.

Content is all that counts–never context. Any book that so much as mentions magic is suspect, even those by Christian fantasists Lewis and Tolkien. (It’s probably just as well the critics don’t seem to have heard of Lewis and Tolkien’s far more mystical colleague Charles Williams.)

Marrs accuses Lewis of “weaving truth and untruth,” foolishly identifying him as a specialist in “New Age metaphysical fiction.” Lewis’s work as a scholar and Christian apologist goes unmentioned. Marrs calls The Lord of the Rings “demonically energized.” Never mind that all the witches in Narnia are evil (the only “good magic” there is divine) and that the wizards of Middle Earth are a kind of incarnate angel.

Michaelson is gentler but suggests that a friendly faun in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe betrays Lewis’s “lifelong fascination with the occult.” She cites The Satanic Bible, of all things, as proof that a faun is equivalent to Pan, “an alter-ego of Satan himself.” (This cliché, usually argued not by Fundamentalists but by neo-pagans, is utterly false.) Why didn’t Michaelson check what Lewis himself says about fantasy creatures in his literary study The Discarded Image?

The stalwart unicorn hunters are curiously feeble in cultural knowledge, seemingly unaware of the classics of the Christian past. What would they make of the fourteenth-century romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which was edited and translated by Tolkien? Since the hero of the poem is an Arthurian knight whose emblem is the pentacle and who learns a lesson in virtue from a denizen of Faerie, is the work Satanic?

These misguided attacks on the fantastic reveal a fear of the imagination, especially the visual imagination. Marrs is so radically iconoclastic that he warns against pictures of biblical scenes, even in the mind.

He would banish the cross itself from Christian churches and objects to representations of it within a circle as being a Satanic/New Age symbol of limiting Christ’s power. (In fact, the enclosed cross in the form of the chi-rho is one of the most primitive Christian emblems.) It requires no acute mind to determine what Marrs and many of his fellow hunters think of Catholic statuary and symbolism.

Behind all this is a fear of human creativity, perhaps even a dread of human nature that inverts the New Age’s exaggerated confidence in human nature. Satisfied they have all important answers, the unicorn hunters don’t want Christians asking, “What if?”

They don’t want them, in Tolkien’s words, “sub-creating” a secondary world of fantasy for “recovery, escape, and consolation.” They can’t see that fantasies such as The Lord of the Rings don’t need an explicit Christian message to point readers toward goodness–and toward God.”

04 June, 2007

"Love is a Fallacy"

One of my friends introduced my sister and I to this story yesterday. It's probably the funniest short story I've read since I roared with laughter over "The Ransom of Red Chief" many years ago.

Love Is A Fallacy

Enjoy!

Love Is A Fallacy

Enjoy!

02 June, 2007

Really awful books

At the library today, the head children's librarian came across the most horrific book. "Daddy is a Monster, Sometimes" - a typical "realistic" 1980s picture book, with dreadfully ugly pictures and a story which revolves around a father who apparantly has a split personality.

Believe it or not, it was in the Father's Day display. Thankfully, Kathleen (the children's librarian) took it out of the collection and put it into the discard pile.

We talked about the idiocy of such books for a while before the library actually opened, and she pretty much reiterated what I've always observed in 1970s-80s "literature" (can I even use the term literature for such bosh?). That kind of literature was produced by a school of thought which was all for "getting everything out into the open". In other words, you should put issues about abuse, disfunctional families, etc, right out into the open in the form of books, movies and other media. I'm going to try not to go into extreme detail, because I have a tendency to do that too much.

One of the most annoying results of this is an incredible predominence of abominable writing. Not that other genres haven't provided opportunities for terrible writers to take a formula and try to use that in place of quality writing. But this one seems particularly suited to that abuse. Many critics (usually of the aforementioned school of thought) praise books about such issues for their "sensitive exploration of difficult issues" or their courage "which enables the author to break through conventions to portray issues too often overlooked". (What a load of bosh!) Well, this type of attitude towards the subject matter is just begging for inferior writers to come along and copy it. (If the subject matter is the bold, original aspect, it should be jolly easy to copy, no?) I can think of one or two good writers who can mangage the realistic fiction for kids genre - Katherine Paterson, for instance. But the majority of the rest rely on the subject alone for "pathos" and "drama"; and the result is insentive bungling.

Another problem: they don't appeal to kids at all. Not only are such books incredibly ugly, but the realism itself is too close to home for kids who may live in disfunctional families, and for those who don't, they're too disturbing. If you really want a book abot disfunctional families, why not read fairy tales? They almost all feature abusive stepmothers, cruel siblings, etc. I can't think of a better example than Cinderella. And fairy tales are far enough removed from reality to not disturb kids.

Well, there are other problems too, but I said I wouldn't go on forever. This isn't supposed to be a dissertation, after all.

Believe it or not, it was in the Father's Day display. Thankfully, Kathleen (the children's librarian) took it out of the collection and put it into the discard pile.

We talked about the idiocy of such books for a while before the library actually opened, and she pretty much reiterated what I've always observed in 1970s-80s "literature" (can I even use the term literature for such bosh?). That kind of literature was produced by a school of thought which was all for "getting everything out into the open". In other words, you should put issues about abuse, disfunctional families, etc, right out into the open in the form of books, movies and other media. I'm going to try not to go into extreme detail, because I have a tendency to do that too much.

One of the most annoying results of this is an incredible predominence of abominable writing. Not that other genres haven't provided opportunities for terrible writers to take a formula and try to use that in place of quality writing. But this one seems particularly suited to that abuse. Many critics (usually of the aforementioned school of thought) praise books about such issues for their "sensitive exploration of difficult issues" or their courage "which enables the author to break through conventions to portray issues too often overlooked". (What a load of bosh!) Well, this type of attitude towards the subject matter is just begging for inferior writers to come along and copy it. (If the subject matter is the bold, original aspect, it should be jolly easy to copy, no?) I can think of one or two good writers who can mangage the realistic fiction for kids genre - Katherine Paterson, for instance. But the majority of the rest rely on the subject alone for "pathos" and "drama"; and the result is insentive bungling.

Another problem: they don't appeal to kids at all. Not only are such books incredibly ugly, but the realism itself is too close to home for kids who may live in disfunctional families, and for those who don't, they're too disturbing. If you really want a book abot disfunctional families, why not read fairy tales? They almost all feature abusive stepmothers, cruel siblings, etc. I can't think of a better example than Cinderella. And fairy tales are far enough removed from reality to not disturb kids.

Well, there are other problems too, but I said I wouldn't go on forever. This isn't supposed to be a dissertation, after all.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)